Gryphons: A Description

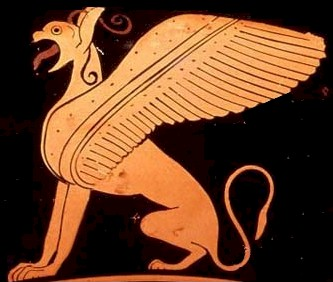

Decorative Griffin, Athenian red-figure kylix, 6th B.C., Staatliche Antikensammlungen

I would like for you to view these two quotes describing the Gryphon. So writes Pausanias, that

"...griffins are beasts like lions, with the wings and beak of an eagle."

And Ctesias writes of mountains,

"...which are inhabited by the Griffons, a race of four-footed birds, about as large as wolves, having legs and claws like those of the lion..."

From these descriptions we find that a Gryphon is either a winged lion with an eagle's beak, or a wolf sized four footed bird, with only the legs and claws which resemble a lion. With these and many other fanciful descriptions, it is a wonder that we can even recognise the Gryphon today! Our general portrayal of the Gryphon however, is one of a lion with an eagle's head, forefeet and wings, and straight horse-like ears. Earlier though, it was hard for the Gryphon to keep a concrete shape when no one had actually "seen" the beast. Thus, the Gryphon has been attributed with the head of a falcon, hawk and eagle, the forefeet of a lion and eagle, and the hind-parts of a panther, dog, and lion. It has had the regular tail of a lion, a lion's tail with feathers at the end, and a serpent's tail. It has had sharp horse-like ears and floppy spainel-like ears. It is shown sometimes with a tuft of beard under it's beak, a lion's mane covering it's neck, and sometimes it did not even have wings. The beak has been sharp and soft, often with teeth or tusks. From it's forehead have risen two horns and a decorative knob. It was also written at various times that Gryphons had red crests, dark blue necks, black bodies, white wings and firey eyes.

The joining of eagle and lion is a natural thought process, since we already associate them both with the regality of Birds and Beasts. Once you stop to realise this, you will find that there are many references to eagles and lions together, and thus Gryphons. One such example is the representations of St. Mark as a lion and St. John as an eagle from the 6th Century Book of Kells, a celebrated calligraphical work of the four Gospels. Writes Ben Mackworth-Praed on the four Evangelical Symbols from the Book,

"The Man is for St. Matthew, in recognition of his emphasis on the human side of the Saviour. The Lion represents St. Mark, who stressed Christ's power and royalty. The Ox or calf stands for St. Luke, a sacraficial victim in token of his emphasis on Christ's priesthood. The Eagle is for St. John, the Evangelist who soars to Heaven..."

The Book of Kells, Saint Mark

It should also be noted that all of the evangelical symbols are winged, thus making St. Mark (a winged lion) alone very gryphonesque. Also, French archaeologist Adolphe Didron described the Pope thusly in his 1854 work, Manuel d'iconographie chrelienne grecque et latine,

"The pope, as pontiff or eagle, is borne aloft to the throne of God to receive his commands, and as lion or king walks on earth with strength and might."

A more modern example is in the lyrics to the song The Last Unicorn (the theme to the movie) sung by America.

"When the last eagle cries,

from the last crumbling mountain,

When the last lion roars,

at the last dusty fountain..."

And ever wonder just why Gryphons have straight ears? Gryphons are a combination of lion and eagle, yet why do their ears look like those of horses, the Gryphon's favorite meal? Writer Michael D. Winkle has found the answer. According to Winkle and the book he consulted, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, the Gryphon's ears stems from the Gryphon's appearence in the Near East.

"The ancient Syrians and Babylonians created the gryphon as we know it, as well as lion-demons, snake-gryphons, bull-men, and other chimerical monsters. Most of these creatures were depicted with long, pointed ears -- specifically, the ears of the Mesopotamian wild ass or donkey."

Click here to read the rest of Winkle's article.

Relatives of the Gryphon

Despite their varied fanciful appearances and names, Gryphons remain unique creatures, embodying a legend and mystery all of their own. The diverse symbolism and distinctive characteristics attributed to these true monarchs of beasts have earned them a place in the world's history to stand apart from all other creatures, mythical or otherwise.

Yet there are other fantastic creatures which resemble Gryphons in either appearance or symbolism, making Gryphons the head of a classification of mythical animals which scholars term "Wondervogel", or in other words, "wonder birds". These fabulous birds of myth and legend are found all across the world, from a variety of cultures and times. Whether they carry gods upon their backs or are simply fowls of gigantic size, these creatures fly though our imaginations to mystify and astound.

Hippogryphs

Roger délivrant Angélique (1824) by Louis-Édouard Rioult (cropped)

The most recognizable relative of the Gryphon is, of course, the Hippogryph, which is in fact the improbable offspring of a Gryphon and a horse. I say improbable because in legend, the horse is the mortal enemy of the Gryphon. Thus, one has to wonder about the mental stability of such a creature. Literally a "horse gryphon", the Hippogryph has all of the qualities of a Gryphon in it's foreparts, and those of a horse in it's rear.

If the joining of two enemies into one sounds poetic, then you are correct. The birth of the Hippogryph can be narrowed down to a line in Virgil's Eclogues (c. 37 BC) as a symbol of impossible love;

"...soon shall we see mate Gryphons with mares, and in the coming age shy deer and hounds together come to drink..."

Again, you can see the strong symbolism attributed to Gryphons also found in Hippogryphs.

The Hippogryph's most noted appearance is in Ludovico Ariosto's epic poem, Orlando Furioso. Atlantes, a magician, owned the hippogryph, but he then gave it to the hero Rogero and taught him to ride the beast with the aid of a magic bridle.

Opinici

The Opinicus is also a creature in close resemblance to the Gryphon, were it not for it's lack of wings and ears, and it's short tail, more camel-like than lion. Since the Opinicus was is a creature created specifically for the art of Heraldry, you can find more information on it in the Heraldry section.

Sphinxes

Another creature closely related to the Gryphon in both appearance and symbolism is the Sphinx. Sphinxes are generally thought of as lions with a human's head, though sometimes they have been found with other animal heads and even wings, which would make them look remarkably similar to Gryphons. Even their symbolism is mutual, since the Sphinx was regarded as the guardians of temples, and was sacred to the sun. And despite the common belief that Sphinxes are purely Egyptian, representations of the creatures have been found from Greece (as in the pic to the right) to the Yucatan. Due to the large number of similarities between the Sphinx and the Gryphon, it has been suggested that the two creatures have a common beginning. In fact, sculptures of Sphinxes appeared almost at the same time that ones of Gryphons did.

Phoenix

De vogel Phoenix, Cornelis Troost, 1720 - 1750 (cropped)

There is enough information on the fantastical firebird the Phoenix to warrant its own website of in-depth exploration as I have done with the Gryphon. Yet until that goal of mine is accomplished, I will seek here to simply familiarize you with this great creature.

Unique in life, the Phoenix has no brothers or sisters, nor mother or father. She gives birth to herself. This bird will live anywhere from 100 to 12,954 years, though the most common life span for her is 500 years. Nearing the end of this time frame, the Phoenix feels the weight of time and knows that her end is near. So she builds herself a nest of spices, herbs, leaves and twigs atop of a date palm and rests inside of it, her wings outstretched. Soon the heat of the sun will ignite the nest, and the Phoenix inside will burn to ashes and die. Yet under the evening stars, life awakens inside of the ashes, and with the morning sun a young Phoenix will fly from the nest, to greet the new day and it's new life with all of the birds of the air flying behind it in homage. There are, of course, variations to this account at varying periods of history.

The Phoenix is extremely thick in symbolism. Like the Gryphon, the Phoenix has been used to represent Christ and his resurrection, and is most recognizable as being a symbol of the dying and rising sun. The very name "phoenix" means "crimson", "date palm", and "Phoenicia", in Greek, proving that to the Greeks that the golden, red and purple Phoenix was the representation of the rising sun in the east, and nested itself upon date palms, which continually renews itself like the fantastic bird.

Our image of a Phoenix rising from the flames has it's basis in ancient heraldry, where the bird is heavily used due to it's symbolism. In fact, such a depiction was used as a symbol of the great warrior maid Joan of Arc, with the motto, "Her death itself will make her live". Alas, like the Gryphon, the Phoenix fell under the discrediting eye of Sir Thomas Browne in his Vulgar Errors (1646), and despite the efforts of Alexander Ross, was finally marked as a figure of fantasy.

Even the Phoenix has a large number of relatives. There is the Egyptian bennu, the keeper of the book of which is and what shall be. The firebird of Russian lore, a bird of jeweled eyes and flowing plumage who stole golden apples from the Tsar's garden. The Bird of Paradise, or Manucodiata, has a brilliant plumage much like the Phoenix, but is footless so that it constantly flies through the heavens and can never touch the sins of the earth. There is also the Cinnamon Bird of Arabia, the Cinomolgus, who makes her nest of cinnamon, a spice once valued as much as gold. And finally, there is the beautiful Feng Huang, emperor of all birds and ruler over the southern quadrant of the sky in China. Actually, the Feng Huang is sometimes regarded in China as two birds, one male (Feng) and female (Huang), who are a symbol of everlasting love since they live together in the Land of Immortals forever.

And yet despite facts and myths, a legend is indeed a legend, left open to interpretation and a wealth of opinions.

Rocs (Rukhs)

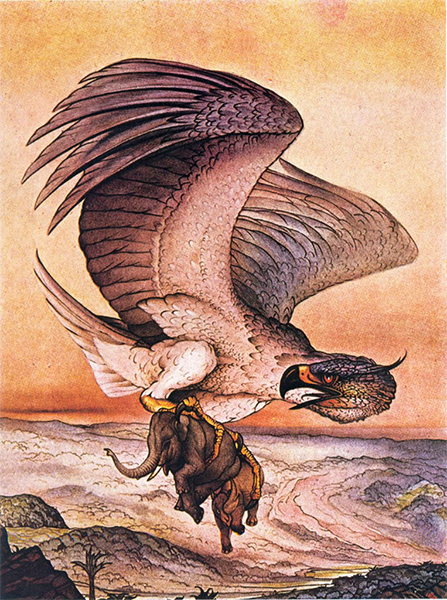

"The roc which fed its young on elephants" by Charles Maurice Detmold, plate from The Arabian Nights, Second Voyage of Sinbad the Sailor (Hodder and Stoughton, 1924).

Rocs are seemingly simple creatures, yet have a complex history. Essentially they are nothing more than large eagles. VERY large eagles. In his written account of his travels, Travels, c. 1294, Marco Polo told of a bird in Arabia so large that it could pick up an elephant and take it into the sky! According to the report of those who have seen them,

...they are just like eagles but of the most colossal size.... They are so huge and bulky that one of them can pounce on an elephant and carry it up to a great height in the air. Then it lets go, so that the elephant drops to earth and is smashed to a pulp. Whereupon the gryphon bird perches on the carcass and feeds at its ease. They add that they have a wingspan of thirty paces and their wingfeathers are twelve paces long and of a thickness proportionate to their length.... I should explain that the islanders call them rukhs and know them by no other name.

For reference, thirty paces would be about seventy-five feet, and twelve paces would be about thirty feet.

Rukhs do have another name however, "rocs". It is in this guise that the large birds appear in The Arabian Nights, where Sindbad meets up with the rapacious elephant eating bird on his second voyage.

The Mahe Group of islands in Indian Ocean were once referred to on a map as the "Islands of the Rukh". This is probably so due to the writings of the Arab traveler Ibn Batuta, c. 1375, who wrote in his journal that,

"What we took for a mountain is the rukh! If it sees us it will send us to destruction."

The winds changed, however, and Batuta never got a good look at what the image was, much to his relief.

There was, in fact, an extinct gigantic bird whose bones have been found in Madagascar, called the Aepyornis maximus. At sixteen feet tall, commonly called the "elephant bird" due to roc lore, the aepyornis laid eggs that would have served an omelet for fifty people! Since the Aepyornis was alive during both Marco Polo and Ibn Batuta's times, it is most likely that this real creature is the base for the fantastic one.

Garuda

A very unique and fantastic creature indeed, Garuda was borne from the cosmic egg along with the eight elephants which support the universe, according to Hindu myth. He is commonly described as a gigantic creature, half man and half eagle or falcon, is brighter than the sun and can traverse the universe with ease. It is the latter fact which grants him the position of the mount for the great Hindu god Vishnu and his consort, Lakshmi.

Garuda is involved in a number of Hindu legends, including just why snakes have forked tongues, a lustful tryst with a human woman, and the resurrection of two heroes with a touch of his wing. In fact, he is the center of attention in the festival of Kumbhmela, which is held in four different places on the shores of the Ganges, the location alternating every three years. This is because each of the four locations are believed to be possible resting places of Garuda during his 12 divine days (years for us) of battling daemons for the pot of nectar of immortality.

Simurgh (Senmurv)

"Zal is Sighted by a Caravan", (Tahmasp Shahnamah, fol. 62v)

The Simurgh, sometimes also referred to as the Senmurv (Dog-Bird), is the ancient Persian Bird of Ages. I should emphasize "ancient" because legend tells that the Simurgh has lived through the destruction and rebirth of the world three times. Thus, because of it's immortal age, the Simurgh holds all of the knowledge of eternity. Though it was initially described as a "gryphon-like" bird, yet with a dog's head, the Simurgh eventually became an enormous bird with a wingspan that could block out the sun and the head of either a man or a dog. It made it's home in the Tree of Knowledge, whose branches held the seeds of every plant in existence. When the Simurgh landed upon the branches it scattered the seeds across the world, replenishing the earth and curing the illnesses of mankind. The Simurgh is also able to cure any sickness to man with a mere touch of it's wings. And in keeping with the theme of duality, where the roc represents the base animalistic and rapacious qualities of the Gryphon, the Simurgh is the benevolent protector and guardian.

The Simurgh makes it's most notable appearance in the epic Persian poem, The Shah Nameh ("Book of Kings"), by Firdausi. It took 35 years to compose the massive (60,000 couplets long) poem, which was completed in 1010 as a gift to Mahmud, the Sultan of Ghanza. In the poem the wise old Simurgh finds a child, named Zal, abandoned at the foot of the unclimbable Mt. Alberz by his father who believed him to be the progeny of demons. The Simurgh takes care of and raises the child, teaching him the ways of the world. Many years later the Simurgh gives Zal one of his feathers when it is time for the boy, now man, to return to the world his father took him out of. Zal returns to his father and inherits his kingdom, ruling wisely with his new wife, Rudabah, by his side. When Rudabah is about to die in childbirth, Zal calls upon the powers of the feather and Simurgh appears to help the woman and she gives birth to the great Persian hero, Rustam.

© 2019 James Spaid. All rights reserved.